Preprint highlighting in a haunted house [Part 1]

Published:

ASAPbio (Advancing Science Access and Publishing in biology) has recently invited me to give a short talk at their monthly Fellows discussion session. Topic of the talk? To share our1 experience highlighting and summarising preprints, and to talk about our editorial decision, back in 2020, to only feature preprints from “peripheral”, “lesser-known”, “non-traditional” labs (quotation marks obliged). In brief: how and why we stopped highlighting work originating within what I now refer to as the White Academic Cosmology. Why this decision? And what does this mean in practice?

This essay/blogpost (/diary?) wants to be a complement to that ASAPbio talk, something maybe a bit more fleshed-out that could also act as a record and a reference for others. A little window into the thought process of two PhD students making their way through academia during an era of preprinting, of statues of racist white men being toppled, and of favourite professors sitting at the editorial boards of journals that charge 3000-12000$ for not paywalling knowledge. While our preprint highlighting editorial decision ultimately came out of a very specific set of circumstances that are unlikely to resonate with many others, there is insight in the reflections brought about by our shunted highlighting practice. A path that others (individuals, organisations, preprint curation services, etc) might be interested in taking and that, in fact, has attracted some interest.

Everything started with an email from our friend Victoria Yan, from ASAPbio, asking us about the practical aspects and obstacles associated with a parsing of preprint literature focused on peripheral preprints. I here want to go over the main points I tried to convey in the long reply I sent her back, and around which I articulated my ASAPbio talk. If the title is a bit unusual (“Preprint highlighting in a haunted house”), it is because I wanted here to source themes, analysis frameworks, and ideas from Avery Gordon’s theorisation of “haunting” and “ghosts” (mainly, but also indirectly of “non-participation”). Themes and metaphors that I here repurpose very loosely but that maybe best gave words to my experience as a student and as a preprint highlighter in the dissonant world of “non peripheral” academia (central academia? Certainly: White). A world where the peripheral is seen in fact as peri-normal, para-normal, haunting. But more on this later.

The house

Like so many other PhD students of the “2016/2017 generation”, we serendipitously entered the (Western) academic world (specifically, that of Developmental Biology) at the same time as it was experiencing new and increasing popular use of preprints and preprinting; certainly, catalysed by the milestone appearance of the biology-focused preprint server bioRxiv. Three/four years ago, bioRxiv manifested itself as a revolution, a long-awaited disruption of the publishing status quo. In this context, initiatives that rallied and empowered early career researchers to curate and highlight these preprints (i.e. initiatives such as the one we joined, preLights) had that exciting flair of undercommons, of revolutionary potential, of an utopic call towards a new united generation of students working in defiance of the monopoly on knowledge dissemination maintained by publishers. We would be Linebaugh’s and Rediker’s “many-headed hydra”, that “motley crew of sailors, slaves, pirates, labourers, market women and indentured servants”2 building our own, rebellious, vision of a fairer publishing academic system. Or at least that was how we were living it at the time.

In fact, preprint and preprint servers were for us mostly holding all of their disruptive and revolutionary power not really in their foregoing of paywalls and all other barriers to knowledge access, but more so in that they allowed barrier-free knowledge “release”. Preprints finally allowed everyone to read research papers without costs, yes, but the very “putting it out there for everyone to see it at no costs” was also free itself. And while this last point may seem expected, and even due, it is in fact under-mining in an academic world dominated by for-profit and not-for-profit publishers pricing open knowledge release through gate-keeping Article Processing Charges. No, everyone will be able to read your science and you can do that at no costs, said preprint servers. Before that, the publisher-prescribed choice of either having to pay thousands of dollars to be allowed to release knowledge openly, or the truly untenable alternative of being allowed to “publish” it at no costs but as something locked behind a paywall. Diamond Open Access journals do not seem to exist for us developmental biologists. In the context of our wider refusal of seeing APCs as something to welcome, celebrate, or even just accept as un-problematic within the global push to open access in its widest (and may I say, intersectional?) acceptation, and informed by wider critical discussions that unfortunately still seem to not have yet reached (or not have reach in) the Western Developmental Biology community, preprints and bioRxiv seemed to us to hold all the potential for a truly equitable, participatory, global, open, empowered knowledge ecosystem.

The haunting

Then we started reading research and metanalyses on preprints. Indeed, some years had passed and the potential of the then-newly-born initiatives had had the time to materialise. A test-run that produced enough data to get an idea of the direction these “disruptive” and “revolutionary” initiatives seem to be headed towards. For our “motley crew” of equitable science hopefuls, an opportunity to reassess our continued alignment with academic movements that had won us for their promised potential. And the metacognition was painful. Because here comes preprint research such as that of Rich Abdill and colleagues3 on the authorship and geographical patterns of bioRxiv and on the use of preprints by the biological community (or to be precise, of that part of the global biological community that uses bioRxiv). And among figures of author collaboration patterns that disturbingly resemble maritime trade maps under colonialism, are bar plots showing a preprint contribution landscape still dominated by western institutions, and biases of major publishers towards the publication (in their journals) of US-produced preprints. The implications are haunting: here is a platform (bioRxiv) that finally allows global biomedical science equal opportunity to be seen… and still only that science produced by Western institutions is the one that will be published by the main journals in the field (and “main” is in fact a code for “western”/”white“). Is the equal opportunity allowed by open platforms only that for non-western preprints to face the brunt of the biases of institutionalised racism, status-quo maintenance, and the unforgiving laws of the Matthew effect that dominate Western academia? And it is like that cartoon metaphor of equity where you give an extra box to the smallest kid so they can see the baseball game on the other side of the fence… just you forgot that on the other side of the fence is a baseball player ready to whack any head that is not what they expected to show up.

We came across papers such as that of Amano and colleagues4, that tells that science-based global policy decisions, mainly affecting non English-speaking countries, are made ignoring the knowledge produced by these very countries (because not produced in English). In fact, it describes a scientific world that only considers English-language science. We read analyses5 showing that when the Western world even just reports on global science, it in facts reports on western science. Under the implicit assumption it is reporting on global science. Here are things as they appeared to be: even when non-Western science can be and is freely broadcasted, it is not published (in the main journals), it is not considered, it is not reported on. These exclusions can’t be an oversight or a bug of the system, they must be a feature of it. They must be an emergent property of it. They are the consequences (likely unexpected, but unexpected by whom?) emerging at the intersection of (or rather from the head-on collision between) Western-born open science equity initiatives and the systems, laws, and incentives of Western Academia. Consequences and biases engineered within academic systems that have the Matthew effect weaved deep into their fabric, within short-sighted APC-based publisher policies that commodify the dissemination of knowledge, within inwards-looking definitions of science and knowledge that in fact do not consider anything non-Western to be capable of producing any relevant form of it. It’s the (self-)blinding light of White Academic Cosmologies. It’s the haunting image of a grotesquely distorted scientific world.

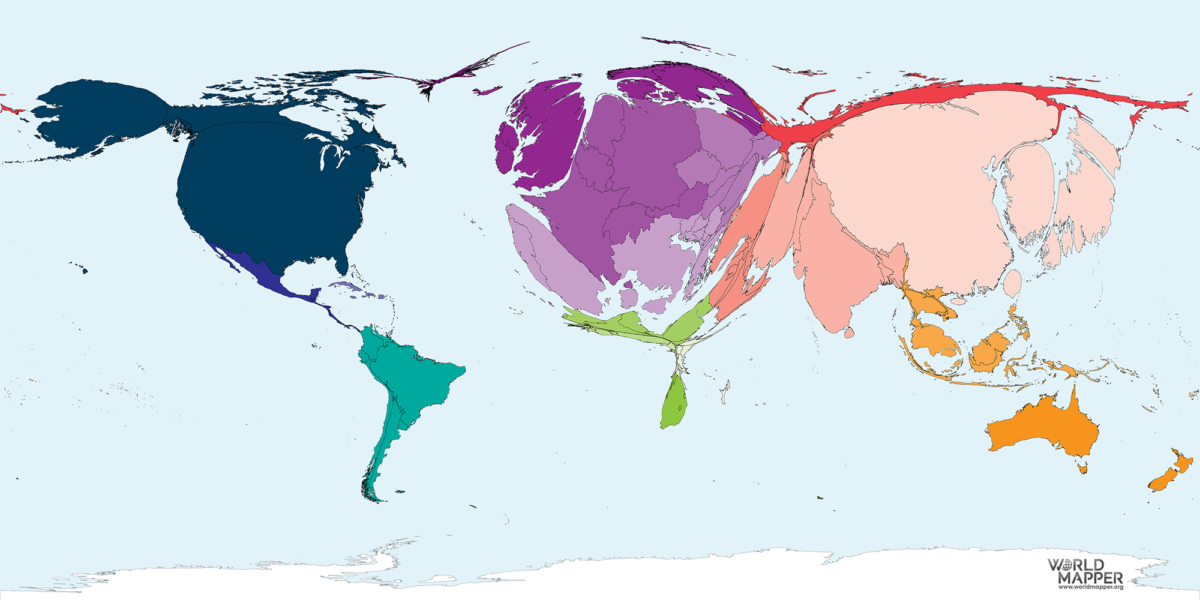

The physical manifestation of such grotesquely distorted world is the map below, indeed often shown during science equity talks. I show it here too for fellow PhD students working within western academic systems (certainly in STEM, but maybe this applies to others too). In fact, they will find it to be the answer to any equity question they might ask themselves, and the experiment starts from being amusing to quickly becoming hauntingly disturbing. The geographical composition of the seminars held at your university? That map. The invited speakers to the big conferences in your field? That map. The invited speakers to the “global”/ “International”/ “Asia-“/ “Africa-“ qualified big conference in your field? That map. The authors cited in the bibliography of the papers you read? That map. The authors cited in your bibliography? That map. The big labs in your field? That map. The best universities for your topic? That map. The historical figures that made big contributions to your field? That map. The origin of your field? That map. The “no-one knew anything about or studied this topic before”? That map. The “global community” of your field? That map.

And then “that map” also becomes the answer to “people benefitting from revolutionary and disrupting publishing initiatives”. Paranormal. But it does not stop there. It is not just who gets seen or seen-as-legitimate on preprint servers: you may start realising that even the preprint curation/highlighting initiatives you were participating in are starting to fall to the appeal of highlighting research that is already under the light. Highlighting preprints that everyone is already talking about. Highlighting the new findings from the big name of the field. These are traps set by the Matthew effect. Again, it’s that map. De Sousa Santos writes that “a certain system of knowledge is hegemonic” when it “convincingly omits the unknowns it lives with” or “generates and credibly denies that there is any other kind of knowledge in any rival cognitive system”6. And when “that map” is the map of everything you see around yourself as you observe the academic systems that surround you, the fact that knowledge also exists outside of it is implicitly denied. It becomes a questionable assertion that needs to be verified. Because otherwise it would mean that this knowledge, that in fact clearly does exist, is being ignored, denied, omitted. Or is just not felt as even missing by most. All of this would certainly feel much less disturbing indeed if relevant science/scientists outside of Western Academia truly did not exist.

The concept of haunting, of being haunted, of suddenly facing the ghosts of a haunted institution, maybe best put words to our experience of cognitive dissonance amongst all of this. Indeed, we were seeing the first ghosts appearing, and from them we were seeing the cracks through which these were slipping through. For the first time we were asking ourselves “whose knowledge, voices, stories, and experiences are being represented; whose knowledge do we consider valid and important, whose knowledge are we learning from?”7, questions loudly resonating in spaces such as the Knowledge Equity Lab but never in our own corners of academia. Haunting is “that moment – long or short – when things are not in their assigned places, when people meant to be invisible or absent or dead show up without any sign of leaving, when the present seamlessly becoming the future gets jammed up, when cracks in the whole infrastructure of repression are exposed” writes Avery Gordon8. It’s that “way we’re notified that what’s been suppressed or concealed is very much alive and present, interfering with us and with the systems of repression that produce concealment and blockage”8. The appearance of ghosts as a manifestation of the many cracks of the establishment. The appearance of ghosts coming from beyond. From outside. From the other side. Making themselves visible and highlighting the tenuous and self-referential foundations of the hegemonic pretences of Western Academia. But the appearance of the paranormal described by Gordon (the perinormal in our case, the knowledge around the expected, normalised sources of knowledge of Western academia) does not paralyse in fear, it does not traumatise. Instead, it forces confrontation, an acknowledgment of existence. It “prompts a something-to-be-done”8.

That-to-be-done

For us, this “something-to-be-done” - within the practicality of our volunteering activity as preprint curators - ended up translating into the decision to change our editorial (preprint-selection) criteria. We just did not want to contribute to a system that was revealing to be not the one we had signed up for. Or, more accurately, we did not want to contribute to the system we had signed up for thinking it would be something different. And if - as the data seemed to show - working within Western academic settings and incentives invariably meant being dragged into the inertia of the status quo and the pull of the Matthew effect, even within well-meaning open science initiatives… well, we decided to refuse that, and we decided to execute such refusal in the reclamation of our agency as parts of this very system. A recent piece by Thirusha Naidu has now given us powerful, empowering words for what in fact we had decided to do: we decided to practice “epistemic disobedience”9.

Other preprint curators may find it important to pause for reflection on their own gatekeeping role (or at least, the risk of it) when selecting, highlighting, “picking up” preprints. And at the same time to pause for reflection on the full extent of their actual agency within such role. But if the broader trends of our curatorial activity were to “highlight” what was being already talked about, if the curatorial activity was to become a further metric of success and thus a goal in itself (see Goodhart’s law), if famous (invariably, Western) PIs were to be mostly the ones getting highlighted, and if engagement with the highlight was to end up being disingenuously co-opted to bring even more attention to an already “lighted” piece, then something needed to be changed. The present could not anymore so seamlessly become the future.

Changing our editorial criteria in fact meant setting up explicit editorial criteria in the first place. And this was an important point, because the previous absence of such criteria did not mean that a covert editorial policy was not being carried out regardless. It just meant that in the absence of a deliberately anticonformistic preprint highlighting choice, we had been highlighting preprints that were already within the light, just under the false illusion of impartiality. Indeed, even if we could truly “randomly” pick a new preprint to highlight from bioRxiv, odds tell that we would end up highlighting US research. Or UK research. And this is without even considering the implicit criteria one relies on when judging a certain preprint as worthy of highlight or unworthy of it. Interesting or not interesting. And how much of this is in fact shaped by positive feedback loops that contain the very light of these highlights within the event horizon of western academic black holes. A closed system that needs to be self-referential and tautological because from these it legitimises its hegemony. “We have decided to deliberately prioritise preprints from lesser-“known” research groups and from historically marginalised scientific communities” read the new disclaimer on our preLighter profile. And through that we found our escape velocity, hopefully powerful enough to break the event horizon of Western planetary systems. Behind it, the firmly held truth that Developmental Biology research exists outside of the walls of Western academia and outside of the gravitational pull of western cosmologies. With the “peripheral” becoming our new centre.

Part I of “Preprint highlighting in a haunted house” ends here. Stay tuned for Part II, which will discuss the practical aspects of identifying and actively seeking “peripheral” science, alternative preprint servers, alternative sources of information, and cultivating broader ecosystems of knowledge. Part II also discusses the “whom for?” of inclusion initiatives like ours. Who benefits from the highlighting of peripheral science? Who really loses from it being ignored? For whom and in the name of whom are these equitable curation activities performed? Finally, Part II will attempt to tackle the big dilemma of “change from within” versus refusal/departure. It will introduce strategies of refusal, disobedience, utopian practice, and in-difference that may well be a lifeline for fellow PhD students torn apart by the institutional violence of Western Academia. .

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The header banner image is by Pawel Czerwinski on Unsplash. World map based on scientific output is from worldmapper.org and licensed under a CCBY-NC-SA-4.0 International License.

These blogposts are written in my personal capacity. The views and opinions expressed here are my own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of my University, my Lab, PI, colleagues, or those of the members of any association or society I am affiliated with. .

When I use our I mean my boyfriend and I. We have been joint preLighters for the Company of Biologists since their early public recruitment calls ↩

Linebaugh, Peter, and Marcus Rediker. The many-headed hydra: Sailors, slaves, commoners, and the hidden history of the revolutionary Atlantic. Verso, 2000 ↩

Abdill, Richard J., Elizabeth M. Adamowicz, and Ran Blekhman. “Meta-Research: International authorship and collaboration across bioRxiv preprints.” Elife 9 (2020): e58496. ↩

Amano, Tatsuya, et al. “Tapping into non-English-language science for the conservation of global biodiversity.” bioRxiv (2021). ↩

Davidson, Natalie R., and Casey S. Greene. “Analysis of scientific journalism in Nature reveals gender and regional disparities in coverage.” bioRxiv (2021). ↩

de Sousa Santos, Boaventura. The end of the cognitive empire. Duke University Press, 2018. ↩

https://knowledgeequitylab.ca/ ↩

Gordon, Hite, Jara. “Haunting and thinking from the Utopian margins: Conversation with Avery Gordon.” Memory Studies 13.3 (2020): 337-346. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

Naidu, Thirusha. “Says who? Northern ventriloquism, or epistemic disobedience in global health scholarship.” The Lancet Global Health 9.9 (2021): e1332-e1335. ↩