Geography of a DevBio bibliography

Published:

You are a new PhD student in Developmental Biology. It’s your first day in the lab and things are still not yet set for experiments to start in full swing. Your PI told you there is one thing you can already do though: a literature search. So here comes the moment you sit down at your computer ready to bookmark journal websites, set up article alerts, subscribe to RSS feeds: it is the time to start scoping out your new literature landscape.

You start by the three journals everyone around you is talking about: “Nature” (published by Springer/Holtzbrinck), “Cell” (by Elsevier/RELX), “Science” (by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, AAAS). You already know you will need to check these regularly. It would be weird if you did not do so - or so you have been told - and in fact you discover your lab even subscribes to physical copies of these. You add all three to your bookmarks.

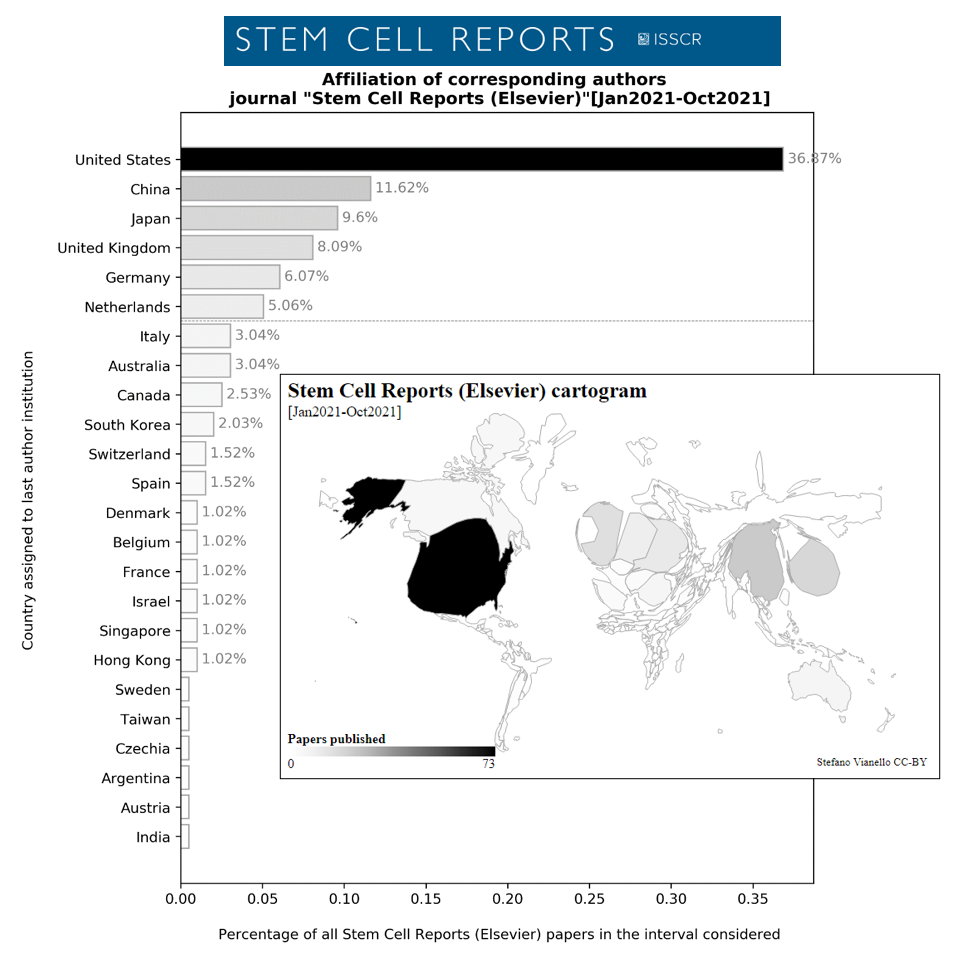

There are journals operated by scholarly societies in Developmental Biology: there is “Development”, published by the Company of Biologists, there is “Developmental Biology”, by the American Society of Developmental Biology (published through Elsevier/RELX), and there is “Cells & Development” (the journal of the International Society of Developmental Biologists, published under Elsevier/RELX). Three more journals to follow. Bookmarked. There are a multitude of other commercial journals by other scholarly societies or not: some that come to mind are “Developmental Dynamics” (by the American Association for Anatomy, published by Wiley) and “Stem Cell Reports” (the journal of the International Society of Stem Cell Research, published by Elsevier).

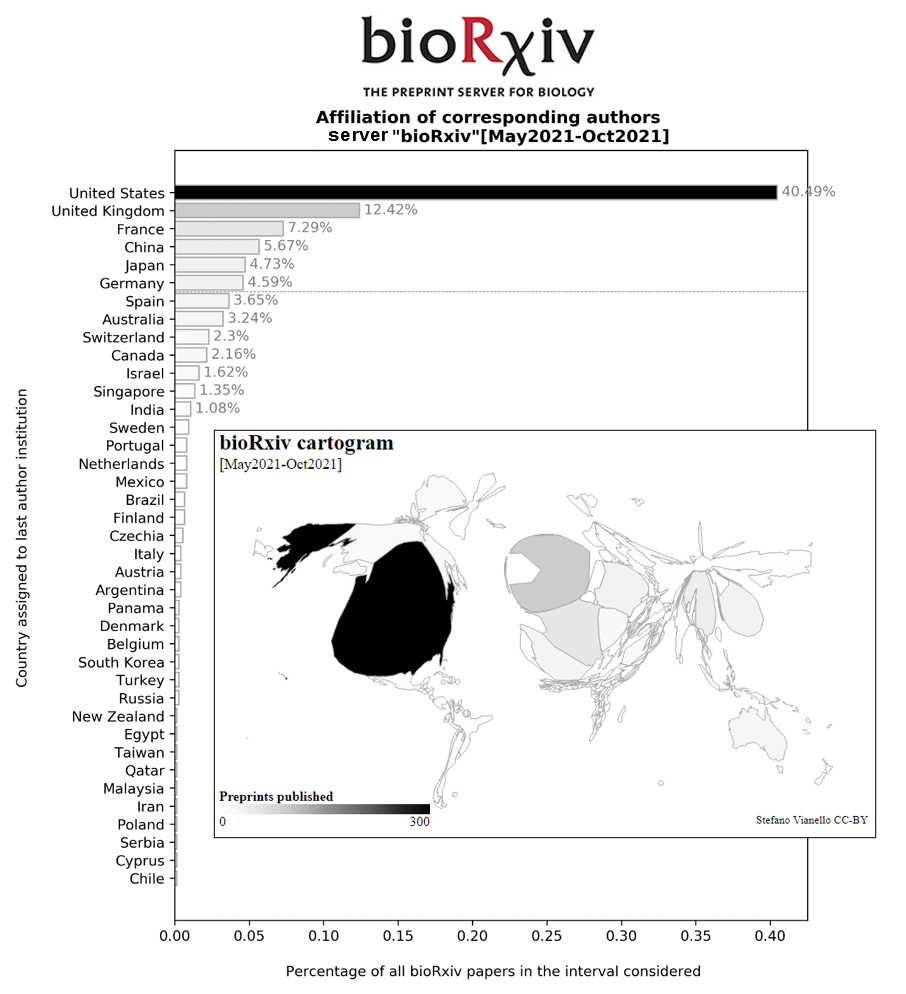

Then of course, it’s 2021: you know most of the research that will be relevant to you will be released as preprints. And there are so many of them! And so here you go subscribing to the bioRxiv alerts on any new post in the DevBio category. You make a mental note to set aside a bit of time every day to have a look for anything new on the preprint server.

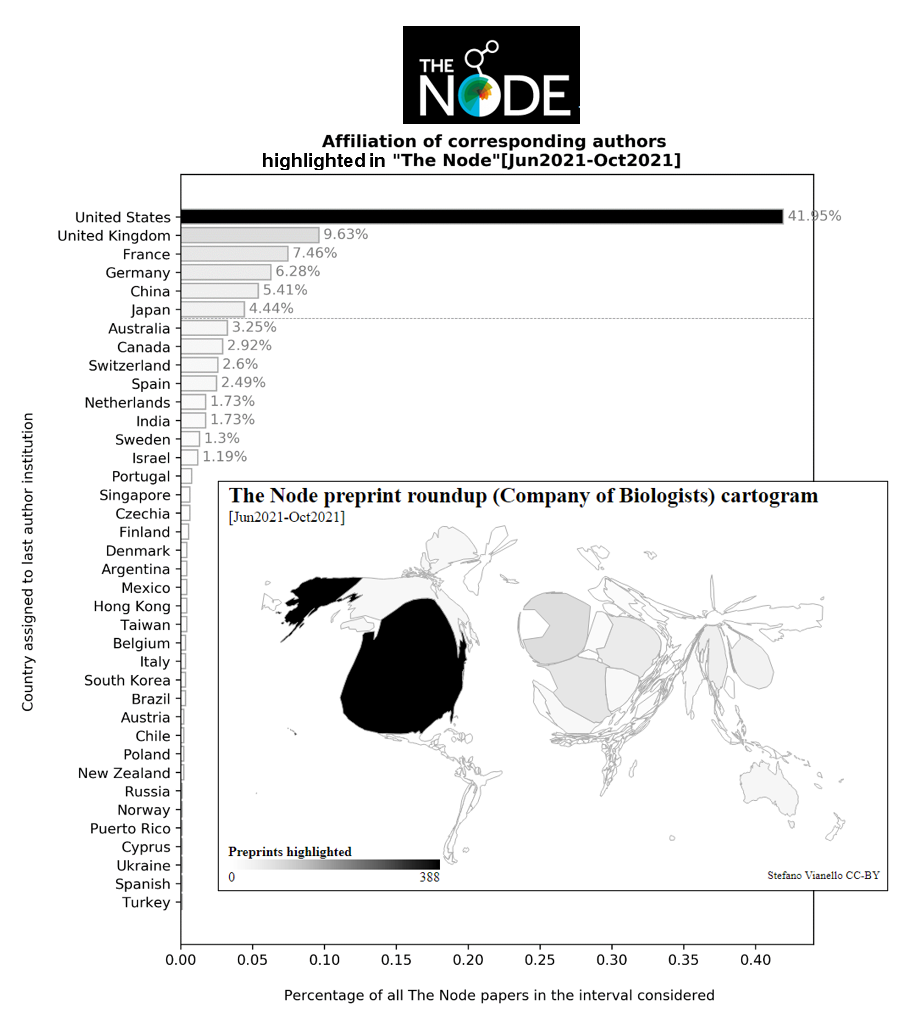

Finally, and to keep up with these preprints, you also discover that community sites, like the Node, do monthly roundups of the most recent/interesting articles in DevBio. International communities of researchers also highlight preprints of relevance through curation activities such as preLights. Sometimes these curated and highlighted preprints pop-up on your twitter feed. New ways to stay updated with the preprint literature and to make it easy to sort through the fast pace of preprint uploads. Liked and subscribed.

Commercial journals, journals by major scholarly societies, preprints, and curation platforms. You have all major areas covered and you are quite confident you are going to manage to stay up to date with the research in the field. You know where to source your information from, and your PI even commends the variety of sources you are looking at. These sources should cover most of the important work in the field, and important work in the field will surely appear amongst either of these sources.

End of scene.

Knowledge equity movements ask us “whose knowledge, voices, stories, and experiences are being represented; whose knowledge do we consider valid and important, whose knowledge are we learning from?”1. And if – as feminist scholar Sara Ahmed writes - citations are “the materials through which, from which, we create our dwellings”2, shall we then have a look at what our DevBio dwelling looks like? The dwelling we have built ourselves and which we are going to inhabit at least for our next 4 years of PhD, if not longer? What can we learn from it? What do we learn from it? What do we learn about who we learn from?

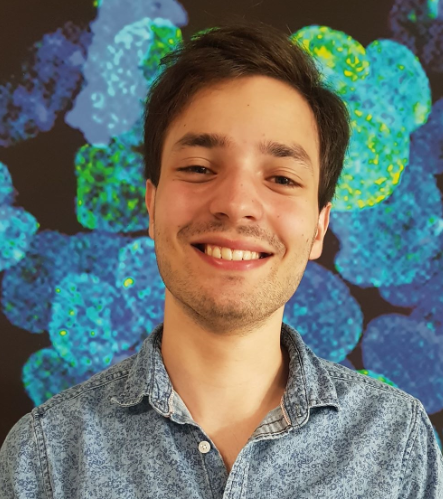

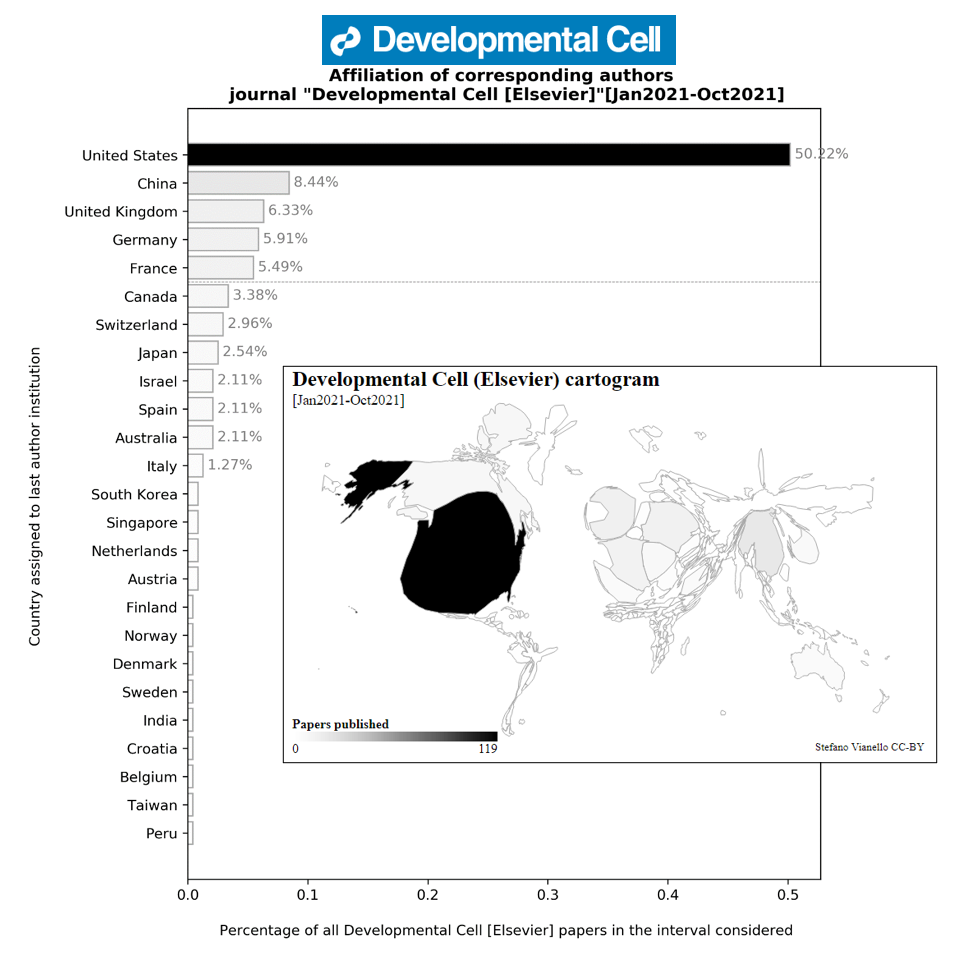

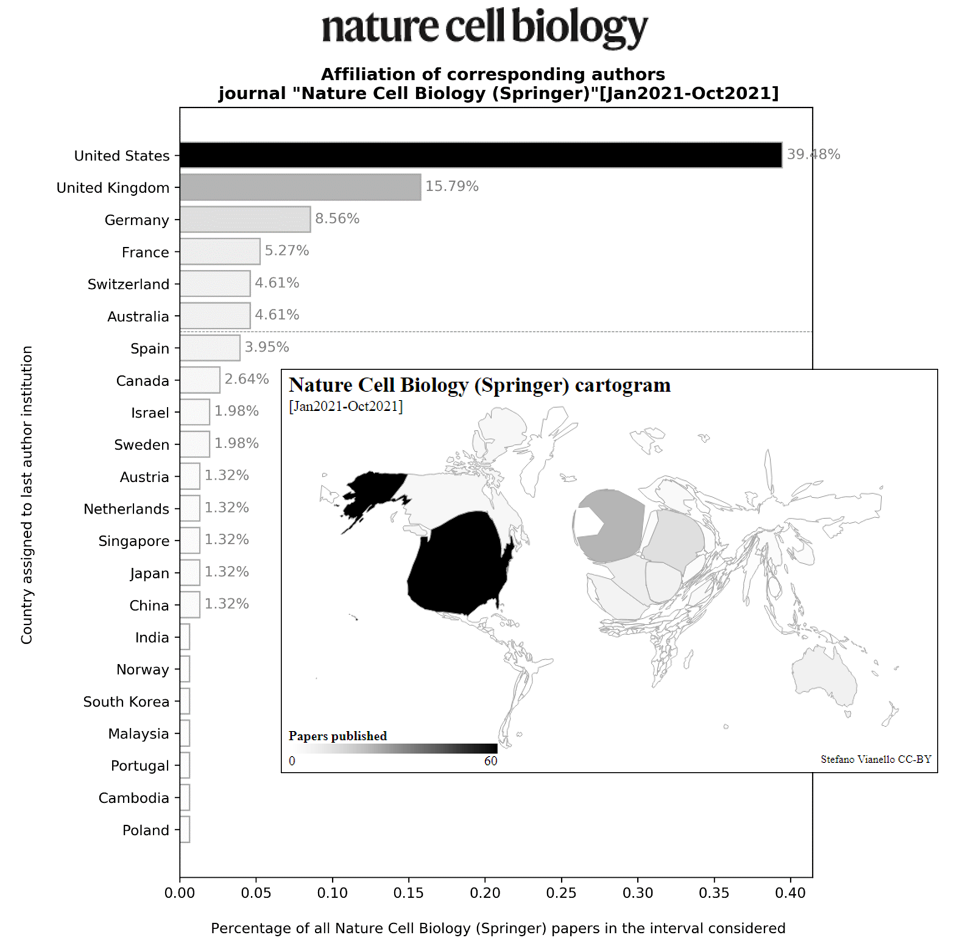

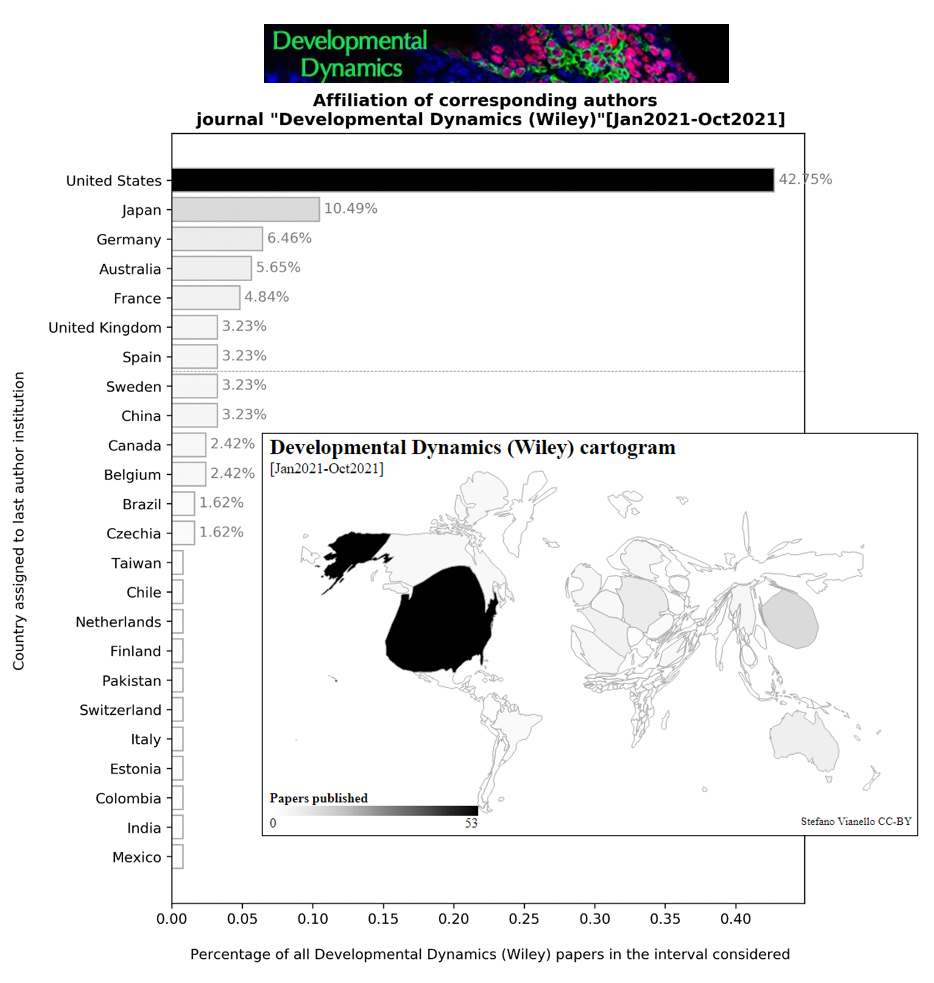

What follow is a DIY bibliometric analysis on the geographical patterns of published DevBio and DevBio-adjacent literature from a variety of sources chosen to span the categories described above (journals, scholarly journals, preprints, curated selections of preprints). Publication sources in each category have been chosen - based on subjective assessment – to represent those that most people in the field would describe as being key publications, and thus those most likely to be recommended as relevant sources of DevBio knowledge to a new player in the field. Because most of the Application Programming Interfaces used only provide geographical information in these terms, the country of origin of each publication has been taken as that of the institutional affiliation of the last (often corresponding) author of each publication, irrespective of the nationality of the author themselves or of that of the other authors in the team. The analysis considers DevBio literature going back – at most - to the beginning of the year, with the assumptions that the major trends highlighted will be consistent across years (note though the unequal burden of the ongoing pandemic on different regions of the world). For processing of larger numbers of papers over longer time ranges and on more powerful machines, I made available the code and source data used to collect and process this metadata and to produce the figures below (at this link). Let me know if you spot any errors!

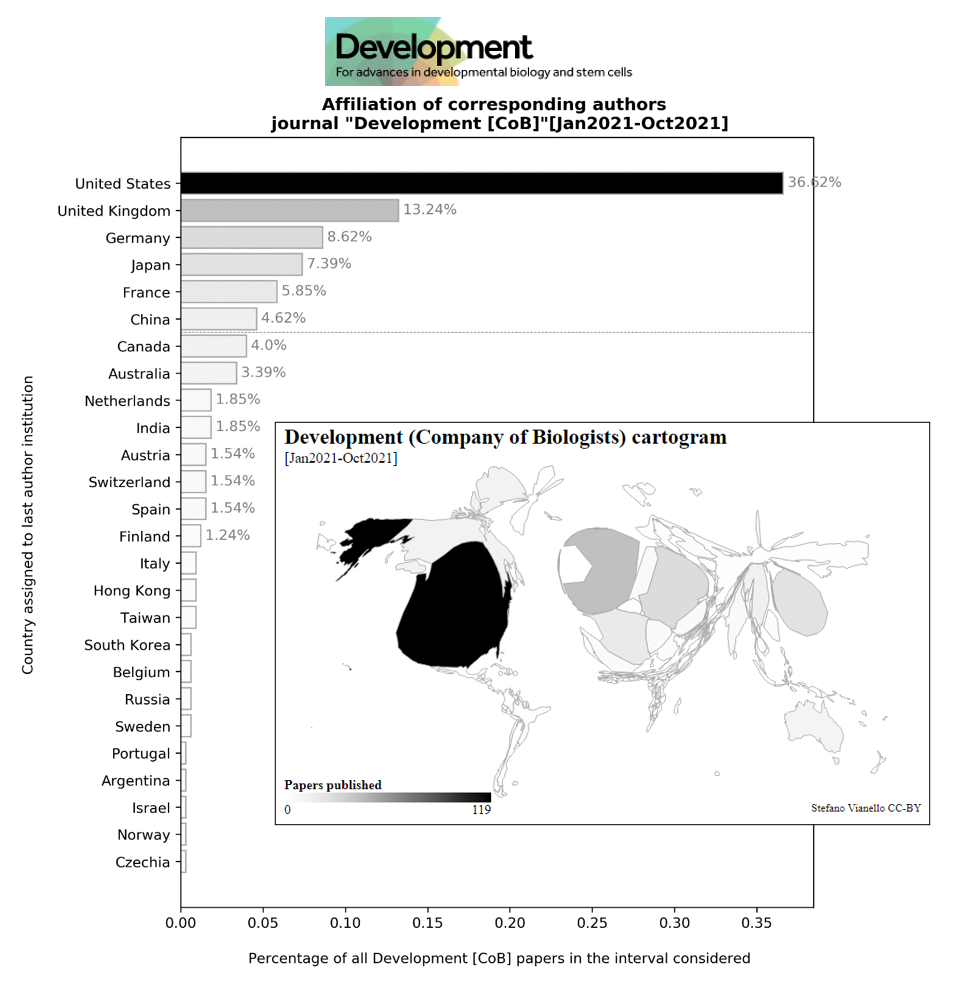

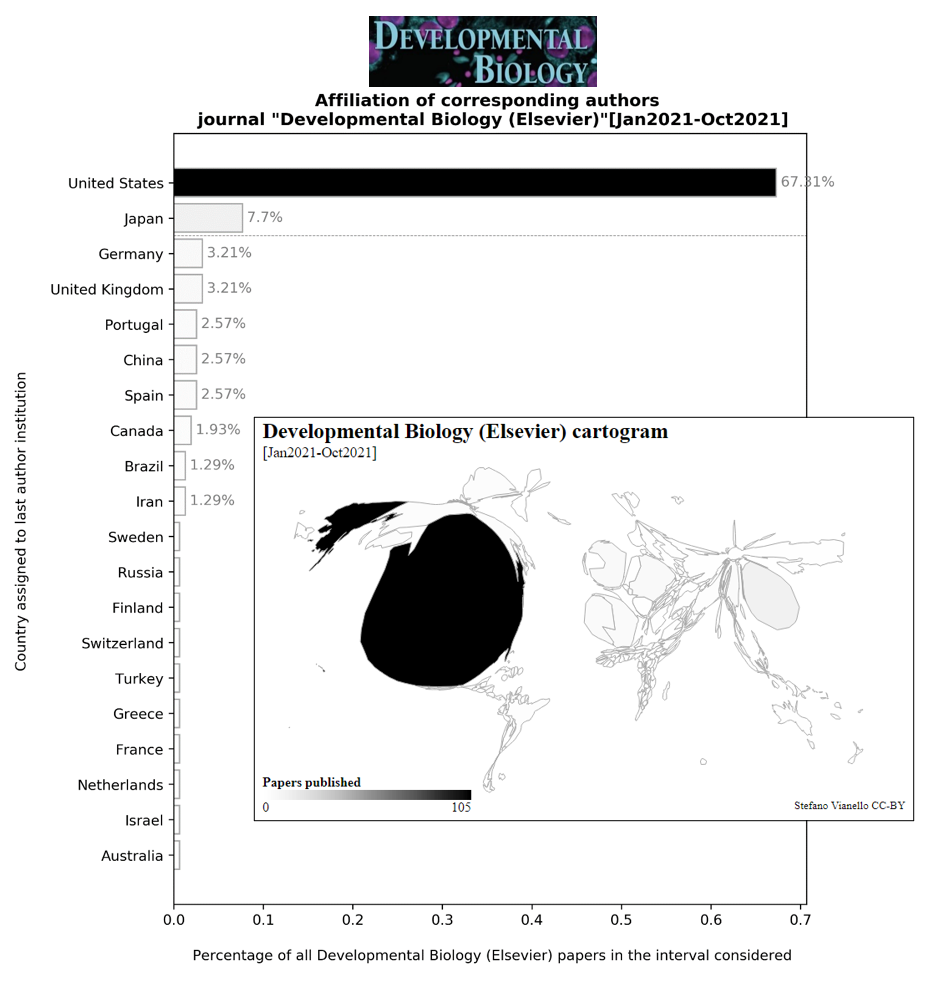

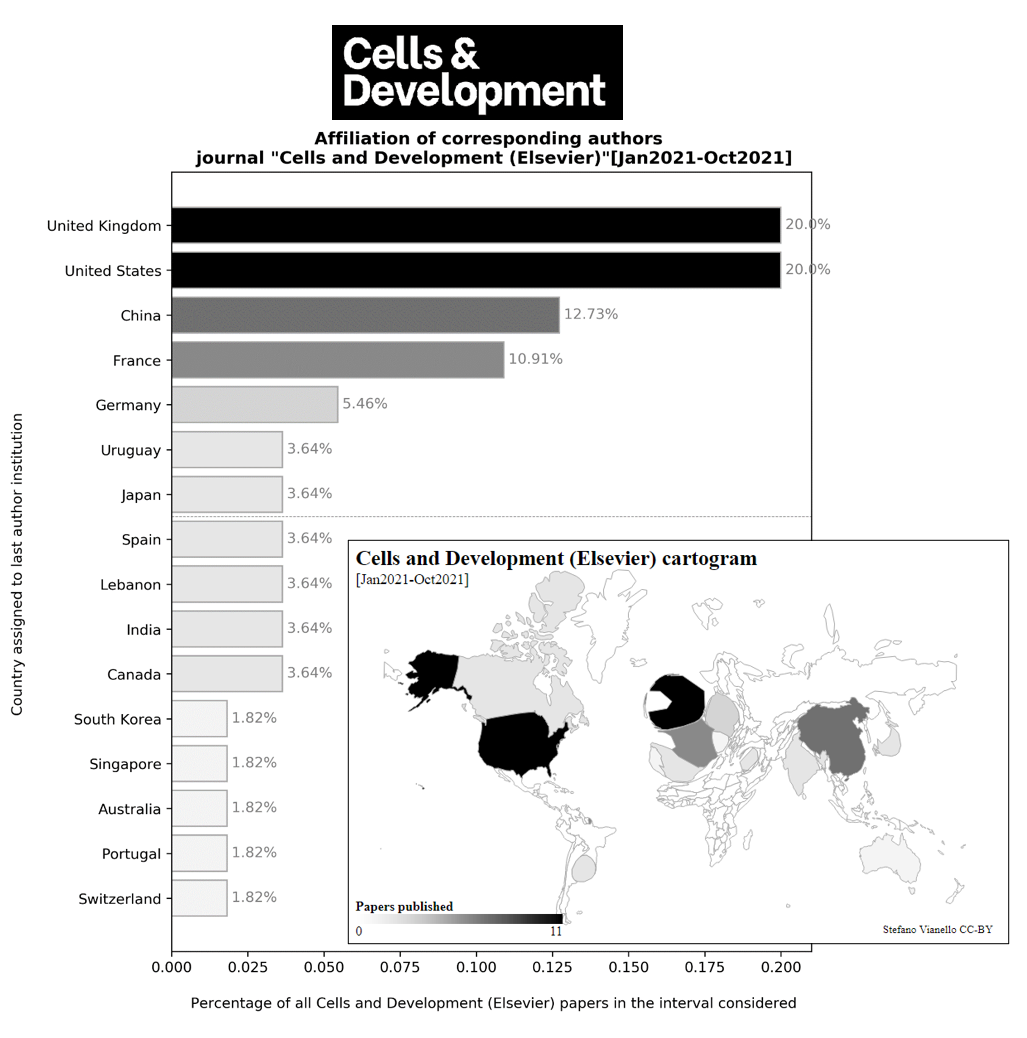

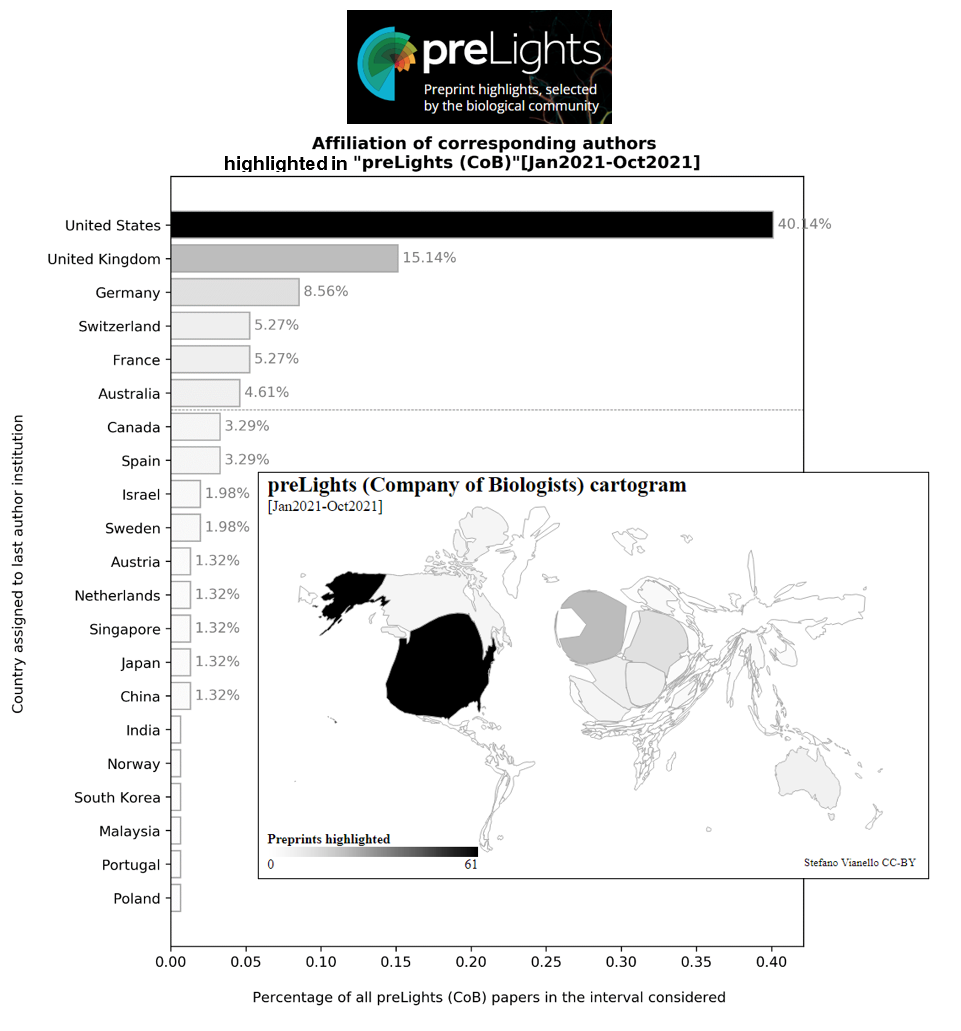

Before starting with the results of this analysis, a quick note on how to read the plots below. Each horizontal bar represents the percentage of all papers published in the timespan indicated (most of the time, from the beginning of this year) with corresponding author from each given country. The exact percentage value, for countries that are represented in at least 1% of all paper corresponding authors, is also indicated to the right of each bar. The color intensity of each bar (from black to white) matches the representation of each country (with respect to the highest represented country, which will thus always be completely black). The horizontal dotted line indicates the cumulative threshold of 75%: 3 out of 4 of all papers published in the given journal will belong to either of the countries above the line. A cartogram map is finally also displayed: world countries are color-coded as in the associated barplot and are distorted as to be directly proportional to the percentage of papers with corresponding authors from that given country (the specific algorithm is detailed here). Countries with high amounts of corresponding authors appear inflated, countries with low or no corresponding authors appear shrunk.

Let’s start our exploration.

International journals

The geography of bibliographies built on mainstream commercial journals, such as “(Developmental) Cell” and “Nature” (here “Nature Cell Biology” given that there is no dedicated subjournal for DevBio) is a common one. As can be seem in the figures below, it is a bibliography centered on knowledge generated in the United States (e.g. 1 in 2 papers published in Developmental Cell this year came from the United States). Aside from United States, research we read in these journals will come from the Global North, specifically Europe, and specifically three countries within it: United Kingdom, France, Germany. Japan and China often also feature in these US-dominated bibliographies. I’ll let you explore the figures below and feel free to use the code to have a look at your journal and timerange of choice.

What is most striking to me is the contrast between the strong effective regionality of the research in these journals (see the cartograms, but also the sudden drop between the US representation and just the second-most represented country in each journal) and the fact that these are not (officially) regional journals, or at least they are not considered to be so. In the academic collective narrative, titles like “Cell” and “Nature” are global/international in scope: these are the title where quality DevBio is found, regardless of the country of origin (or so this is the assumption). For some journals this implicit international scope is explicit, as in the case of Elsevier’s “Stem Cell Reports” (from the International Society of Stem cell Research). Even these titles hardly published any paper from any continent outside of the global North this year.

What comes through (and will be a recurring trend throughout) is strong regionality of bibliographical content without explicit indication of such regionality (or actually with indications to the opposite) if such regionality involves the Global North. In fact, the question on whether there is an implicit process of equating the United States/UK with globality is, to some extent, rhetorical. In “The end of the Cognitive Empire” B. de Sousa Santos identifies “the superiority of the universal and of the global” as one of the defining monocultures of modern Eurocentric knowledge3, which thus not only erases anything perceived as “local”, but in fact prescribes universal/global character to local realities when local = Global North. In this optic, research from the US/Global North can indeed be research from “all over the world” in definitions of the world that only have US/Global North in it. The scientific output of the US/Canada/Europe/Japan/Australia can indeed be “international” if these are a fair sample of the nations in the world (that produce DevBio). To what extent do international journals (and bibliographies) dominated by US(/UK/French/German) DevBio research reinforce the idea of a world where these are the only countries where DevBio (or even worse, quality DevBio, relevant DevBio) originates from? To what extent do they build that world? There is a lot of unlearning and critical distancing we have to do as consumers of these bibliographical sources.

Scholarly society journals:

Similar patterns can be seen in the DevBio knowledge we can source from the main scholarly society journals. Mostly because the main scholarly society journals are those of the US and UK (why? And to what extent are these patterns self-reinforcing?). It is thus expected that the journal of the American Society of Developmental Biology (Elsevier’s Developmental Biology) almost exclusively published papers from the US (short of 70% of all papers, the highest regional skew in all datasets analysed). Development, from the (UK) Company of Biologists, also expectedly mostly offers US and UK DevBio research. Again though, the reality of the research published by these scholarly societies contrasts with the apparent global/international makeup of the communities that rally under them, and in fact contrast with claims of representing- (or genuine aspirations to represent) the global DevBio community. If interested in the DevBio from other regions of the world, one would thus have to turn to journals from DevBio societies of other countries (more on this later). Would these other journals immediately assume a “local” dimension? Could/do these journals become associated with the same assumptions of global relevance as e.g. that of Developmental Biology?

It is interesting to note that more explicitly international publications, such as Elsevier’s Cell&Development (from the International Society of Developmental Biologists) showed a more restricted number of countries represented (likely tied to the lower number of publications per year), but a much more balanced representation of papers amongst those countries. Again, international still seems to equate UK/USA, but DevBio from e.g. Uruguay and Lebanon was notably presented to readers of the journal this year.

Preprints:

While the geographical patterns of knowledge production reflected in commercial and non-commercial journals may not be totally surprising given the inequalities and gatekeeping of knowledge dissemination built-in by the publication- and business policies of most of these journals, the analysis of the geographical landscape of Developmental Biology preprints might be more surprising. While bioRxiv preprints show a much wider variety of country representation (and this within an even shorter timespan than that considered for the journals above), extremely similar patterns are immediately visible and in fact have been already highlighted by much more focused and thorough investigations (see Abdill et al; 2020). There are no immediate barriers to publication on bioRxiv, and bioRxiv does not have geographical restrictions: still, 3 out of 4 preprints uploaded on the bioRxiv DevBio section will document US/UK/France/Germany/Japan/China research, with 40% of papers from one single country alone, the US.

Preprint curation initiatives:

To this point, preprint curation and highlighting initiatives have the most immediate potential to contest the bibliographical status-quo and to bring to the front DevBio research from the true global community, rather than continuing to highlight dominating research. This is because the agency that comes from curatorial activity allows the intentional selection and presentation of research that may be minoritary (or minoritised) in the current landscape. Preprint curation as a tool against the Matthew effect (I discuss my own attempts and explorations within this space in a previous blogpost). Still, literature curation does not inherently subvert the status quo and does not inherently present richer sources for more diverse and comprehensive DevBio bibliographies. If curated list of preprints are to become a proxy to relevant work for researchers that do not have the time to sort through preprint servers, then curatorial activities also carry the risk of prescribing selected preprints as representative of the literature in the field. Preprint curation as a medium for the Matthew Effect.

A researcher that follows the monthly preprint roundup of the Node will understandably be exposed to a bibliography that matches the unequal regional distribution of DevBio preprints available on bioRxiv (because these convenient roundups aggregate all DevBio papers made available on the preprint server). It is however important to reflect on the implications of presenting such regionalised research in platforms with implicit or explicit community claims (e.g. “for the community by the community”). What are the implications of truly global communities of DevBio scholars being exposed to globally-biased research bibliographies? Which community is, in fact, the DevBio community? And which community is DevBio research for? How are these communities represented or not represented in the literature they are exposed to? In the absence of explicit reflections on the regionalisation of our bibliographic landscapes, DevBio community-spaces risk reinforcing tacit associations between globality and Global North.

Conclusions:

At the end of this DIY bibliometric exploration it is clear that the bibliographical landscape is very similar in all sources. A typical DevBio researcher (keep in mind my positionality here in defining “typical” as Western) will mostly be exposed to research from a very limited number of countries. Mostly the US, otherwise France, Germany, China, Japan. Note however that this data cannot and does not speak about bias. Asymmetric representation of DevBio research from the US in a given journal does not necessarily imply bias, especially given the backdrop of the unequal scientific output of different countries around the world. That is, in a global context where scientific production is asymmetrically distributed, unbiased publications will reflect such asymmetric distributions in the form of asymmetric bibliographies. In fact, and as shown, even the barrier-free preprint server bioRxiv is overshadowed by research originating from the US. Having said that, research has shown that many “major” journals do indeed show a bias towards US research compared to the number of preprints available on bioRxiv (Abdill et al; 2020), and biases clearly do exist at all levels of the academic knowledge production pipeline. The very underlying asymmetric distribution of scientific output ultimately derives many of its drivers from the colonial history and neocolonial exploitation of global “peripheries” by most if not all of the big scientific producers highlighted here. It also derives from systemic and institutionalized racism, bibliographic negligence, citation amnesia, Mathew effect (see e.g. Chima, 2021 and references within). Still, bias is not what this data can speak about.

— “Silences enter the process of historical production at four crucial moments: the moment of fact creation (the making of sources); the moment of fact assembly (the making of archives); the moment of fact retrieval (the making of narratives); and the moment of retrospective significance (the making of history in the final instance). Michel-Rolph Trouillot5

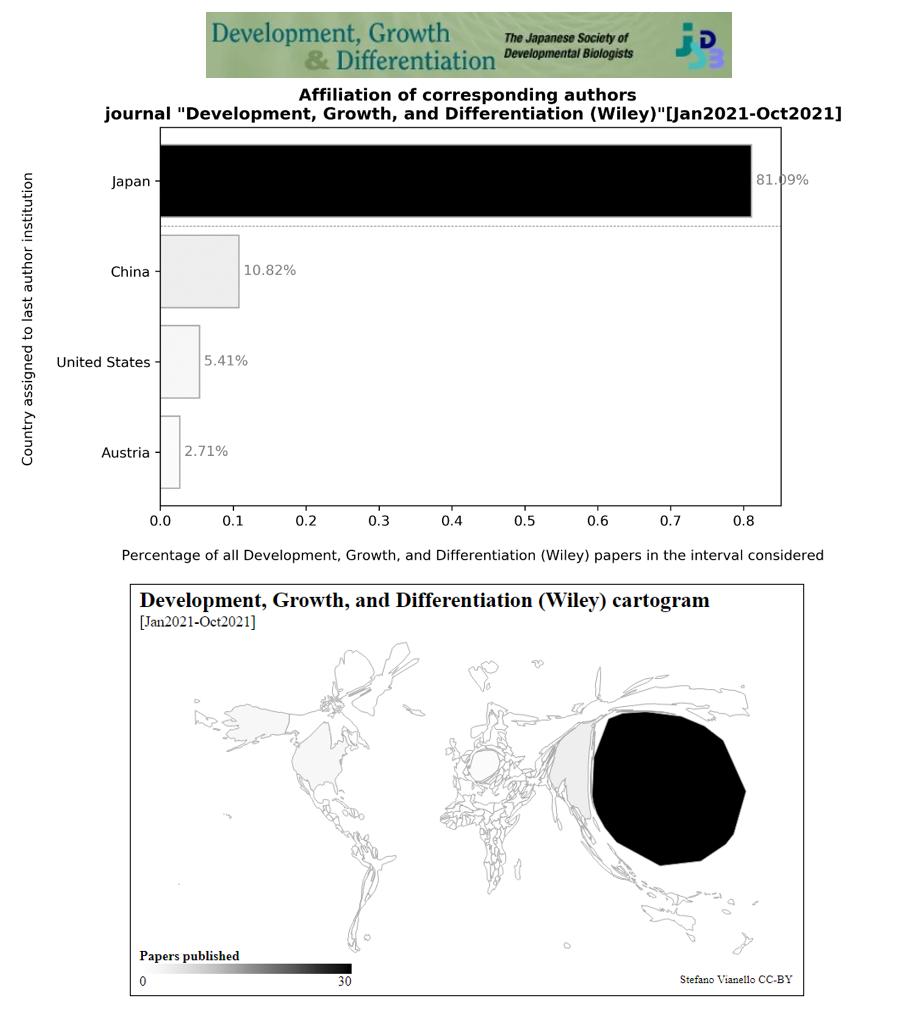

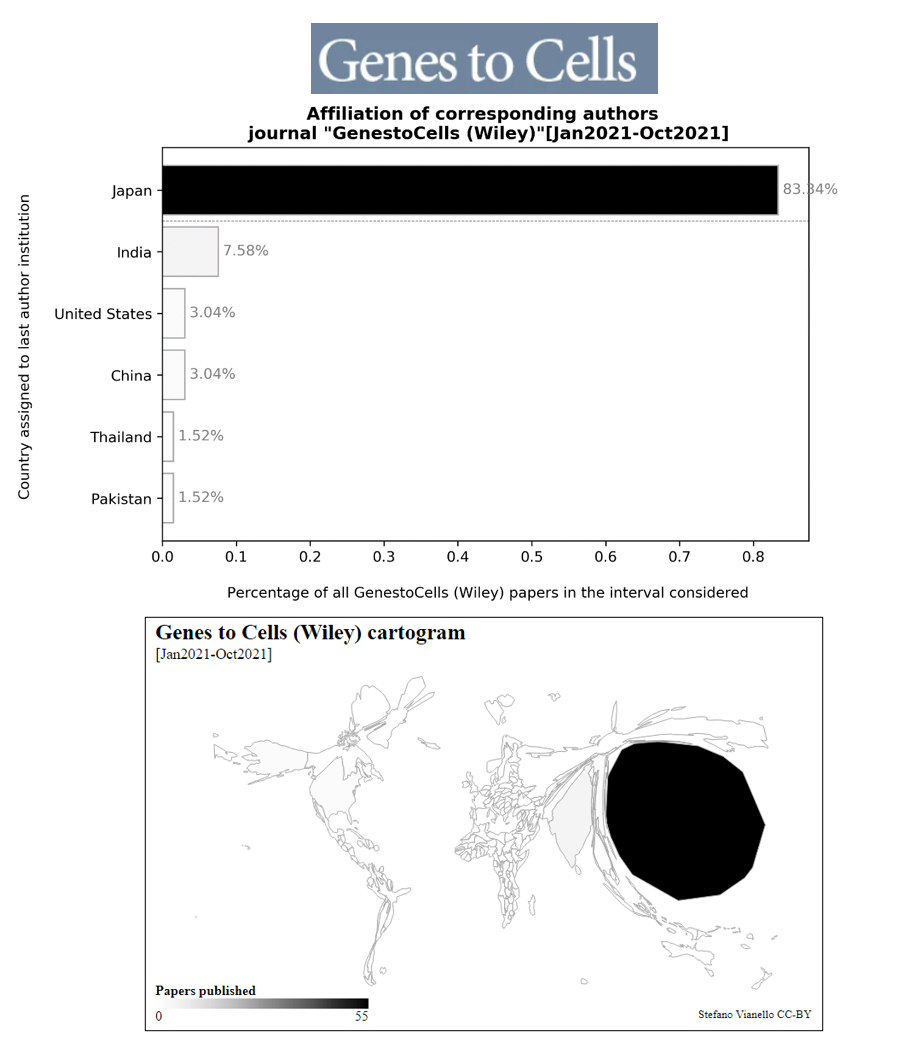

Second point is that bias/focus (in the form of highly skewed DevBio bibliographic distributions) is not the problem in itself. Indeed, it is coherent for the journal of the American society of Developmental Biology to feature and showcase US science (as is the case). Similarly, the journal of the Japanese Society for Developmental Biologists “Development, Growth & Differentiation” (published by Wiley) almost exclusively collects Japanese DevBio research. The same applies for “Genes to Cells” (Wiley), also with a clear Japan bibliographical focus. To take an example from non-Global-North countries, the Philippines Journal of Science would likely show, as expected, an equally skewed bibliographical landscape of DevBio research produced in the Philippines. The fact that I cannot easily obtain such data because this journal, like many non-Western ones, is not listed in the main indexing databases is a further element to the discussion. Ideally thus, DevBio researchers would be aware of a wide variety of country-focused DevBio journals building together a complete view of the progress in the field. Why is this not the case? Why are US- and UK- focused DevBio journals the one that are “known”? And why do US- and UK-focused journals appear as globally representative in the academic collective? Why do international journals end up presenting skewed bibliographical sources to their readers? These are the points that would be interesting to discuss and to have always in mind.

These maps are maps of where the knowledge comes from in current Western research. Even for the thought-case presented at the beginning of a researcher organising around comprehensive and orthogonal sourcing approaches. Even if following curation initiatives by diverse community members. What are the worlds that these maps build? What are the implications of this? How does these patterns perpetuate and strengthen the idea that DevBio is in fact a US/EU/Japanese enterprise? How does this transform the existence of DevBio in other countries as something to be verified, or as something that might in fact not be true? Does this explain why most international DevBio conferences only have speakers from these same countries? How does the DevBio that exists in Latin America, Africa, South East Asia, Middle-East, Eastern Europe translates to the citation record?

What this data inspires me to ask is: given that such a big asymmetry exists in the DevBio literature we consume, how can we organise and operate around it? Why do none of the DevBio publication venues that come to mind present bibliographical maps that do not have the Global North at its centre? Where do we have to look at for maps different than the ones you have been scrolling past throughout this whole blogpost?

— “We learn from who is not heard about who is deemed important or who is doing “important work” […]. We learn how only some ideas are heard if they are deemed to come from the right people; right can be white.” Sarah Ahmed6

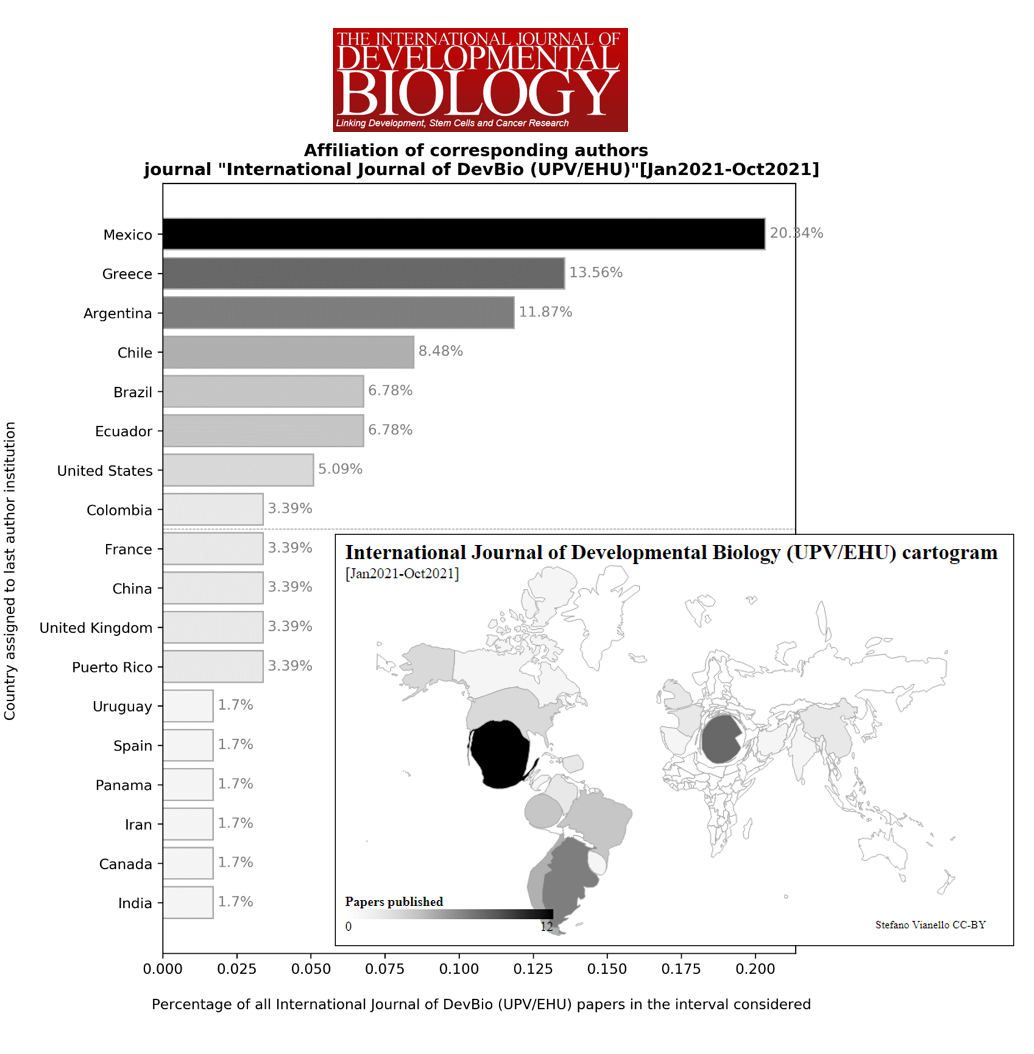

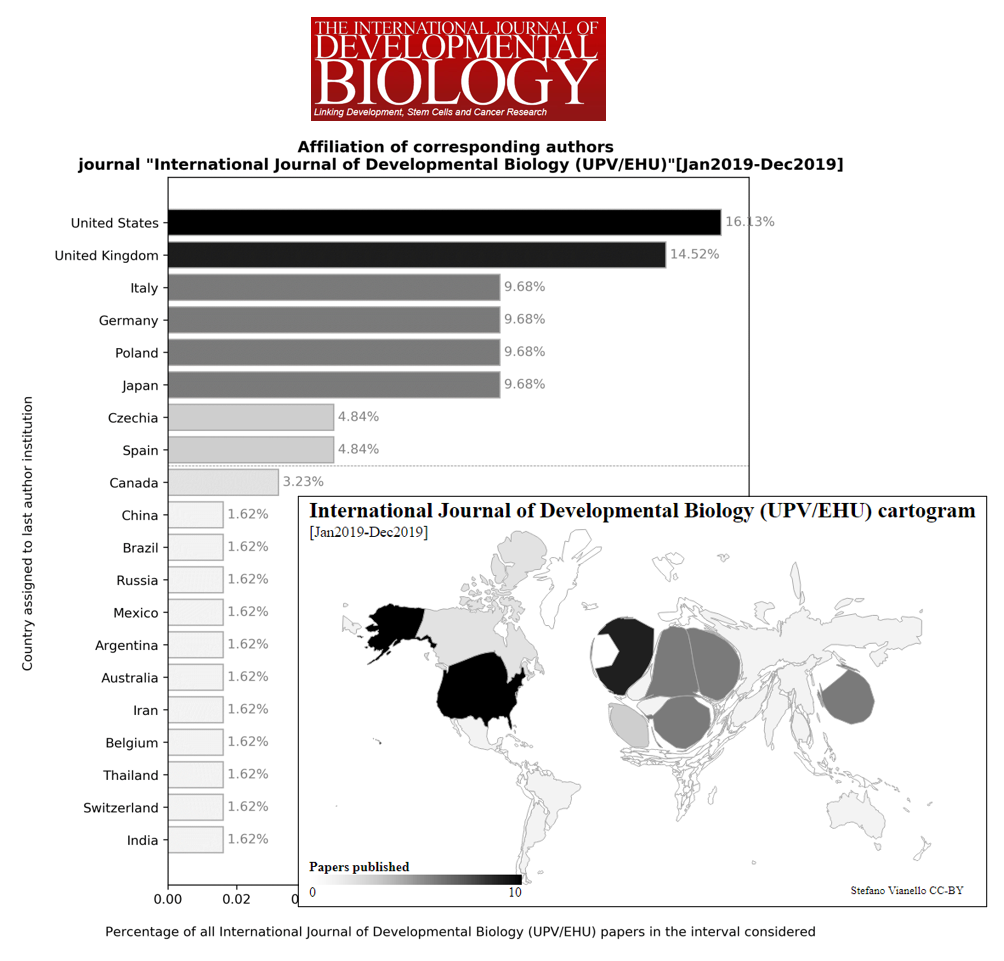

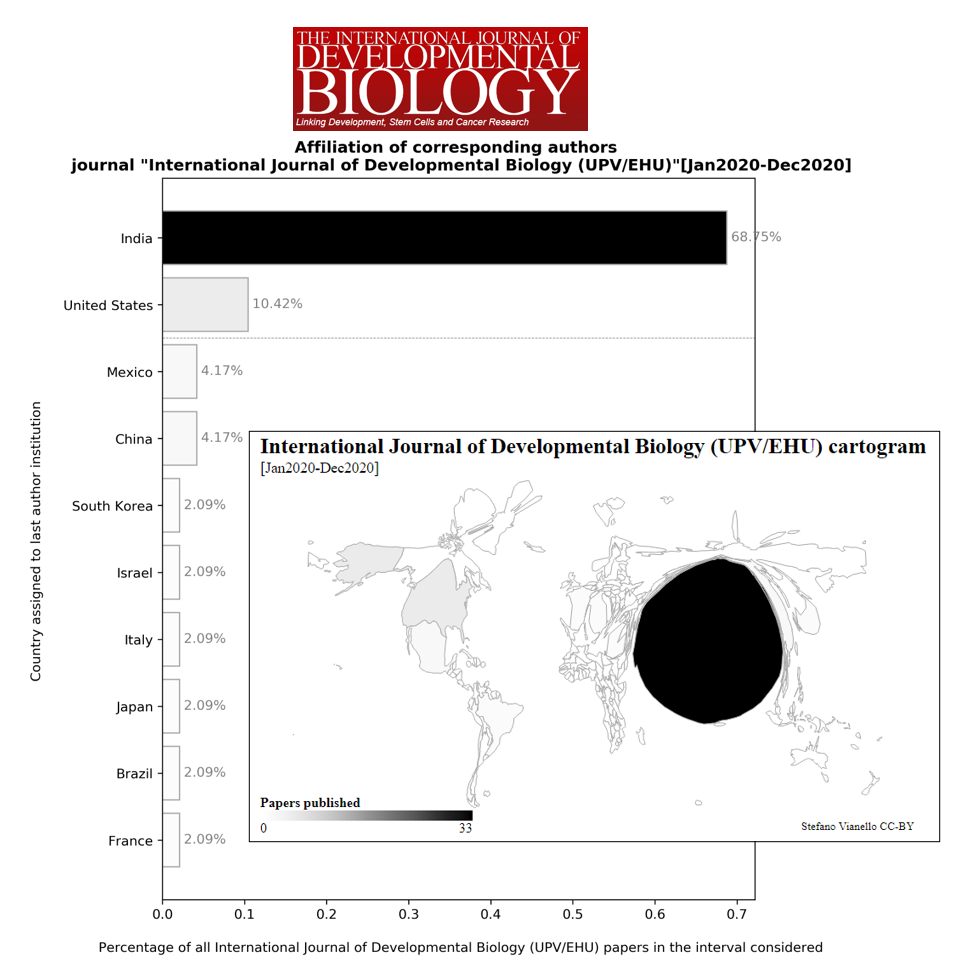

So, which publications should we add to this list of hypothetical sources for an incoming PhD student? What is the true extent of the DevBio reading landscape? This I do not know but it is something I am excited to explore. An interesting case study is that of the “International journal of Developmental Biology” (published by the University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU), which shifted from the usual Global-North-centred map (though with less skew towards either country represented, see first plot, 2019 data), to a finally different content and presenting to its readers DevBio produced in India (2020) or Ibero-America (2021). These refreshing maps, the first ones not dominated by the US or Global North in this entire analysis, comes from the decision (note how intentionality comes to play) to dedicate special issues to Indian and Iberoamerican DevBio. The question then is: how do we transition from non-Global-North DevBio being “special-feature” of an international journal to it being an integrated part of the literary landscape?

What other sources could we further look in? There are all the journals on bioline international, there is the AJOL repository (African Journals Online), there are DevBio journals in Africa and South East Asia. There are preprint servers that are not bioRxiv, there is RINarxiv, OSF preprints, AfricArxiv. SCIELO preprints. There are the articles on Redalyc. In fact, there is DevBio communicated in languages other than English. There is DevBio communicated through other means than papers and codified academic formats. Since it is true that “we are all developmental biologists”7, let that be coherent with the literature we read and cite. Asking ourselves “where do we have to look for the “rest” of the DevBio literature?” brings forward the crucial realisation that we have to look for it. We. We have to do it. The DevBio literature that is “looked for” on our behalf is the one described in all of the maps above, and is not complete. DevBio exists outside of the US, France, Germany, and Japan. And why does no one come up to us to ask us “wait a minute, have you only been reading US and European DevBio for the past 4 years? How is that?”, and maybe that person - for the moment - needs to be ourselves.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The header banner image is by Brandi Redd on Unsplash.

These blogposts are written in my personal capacity. The views and opinions expressed here are my own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of my University, my Lab, PI, colleagues, or those of the members of any association or society I am affiliated with. .

https://knowledgeequitylab.ca/aboutus/ ↩

Ahmed, Sara. Living a feminist life. Duke university Press, 2016. ↩

de Sousa Santos, Boaventura. The end of the cognitive empire. Duke University Press, 2018. ↩

https://scicomm.plos.org/2021/06/02/prelights-highlighting-preprints-from-and-for-the-biological-community/ ↩

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph; Silencing the Past (20th anniversary edition): Power and the Production of History (ed. Beacon Press, 2015) - ISBN: 9780807080542 ↩

Ahmed, Sara. Complaint!. duke university Press, 2021. ↩

Wallingford, John B. “We are all developmental biologists.” Developmental cell 50.2 (2019): 132-137. ↩